Diverse movements around the world have been pushing for an end to ecological diminishment for decades, centuries even. In response states worldwide have committed to thousands of environmental domestic laws and international agreements. Ecological losses have largely only worsened.

The extinction paradox represented in two graphs: on the left, the number of domestic laws concerning endangered species, globally, 1970-2020 (data source: ECOLEX database); on the right, global wild vertebrate abundance (conservatively represented by the Living Planet Index), 1970-2014 - the graph shows a 60 percent decline in wild vertebrate populations since 1970 (data source: WWF 2018).

How can this paradox of escalating loss in a time of proliferating formal protection be explained?

Endangered woodland caribou in Canada exemplify this paradox.

Caribou are one of the most protected, well-studied species in the country, but studies suggest that “all caribou in Canada are currently at risk of extinction,” with some populations likely to face extinction in our lifetime. Many herds once numbering hundreds have dwindled to mere dozens; others are completely extirpated, including seven herds in BC lost since caribou were listed as endangered two decades ago.

“All caribou in Canada currently are at risk of extinction”

— Dr Justina Ray, Director of the most recent independent scientific assessment of caribou in Canada

Caribou in northeast BC.

Photo credit: Chris Johnson

Why amid all this research and policy are caribou populations on a downward trajectory?

The proximate answer is the protective laws have not slowed industrial development driving caribou declines.

Our and others’ research shows that federal and provincial governments continue to not only approve but often subsidize extractive developments in critical caribou habitat.

Here are three examples

one

Between 1995-2017 federal and provincial regulators approved 64 out of 65 major projects - mines, pipelines, dams - with potential adverse effects for caribou and the one rejection had nothing to do with caribou. This despite a litany of potential impacts to caribou - including wiping out the remaining caribou in certain herds.

two

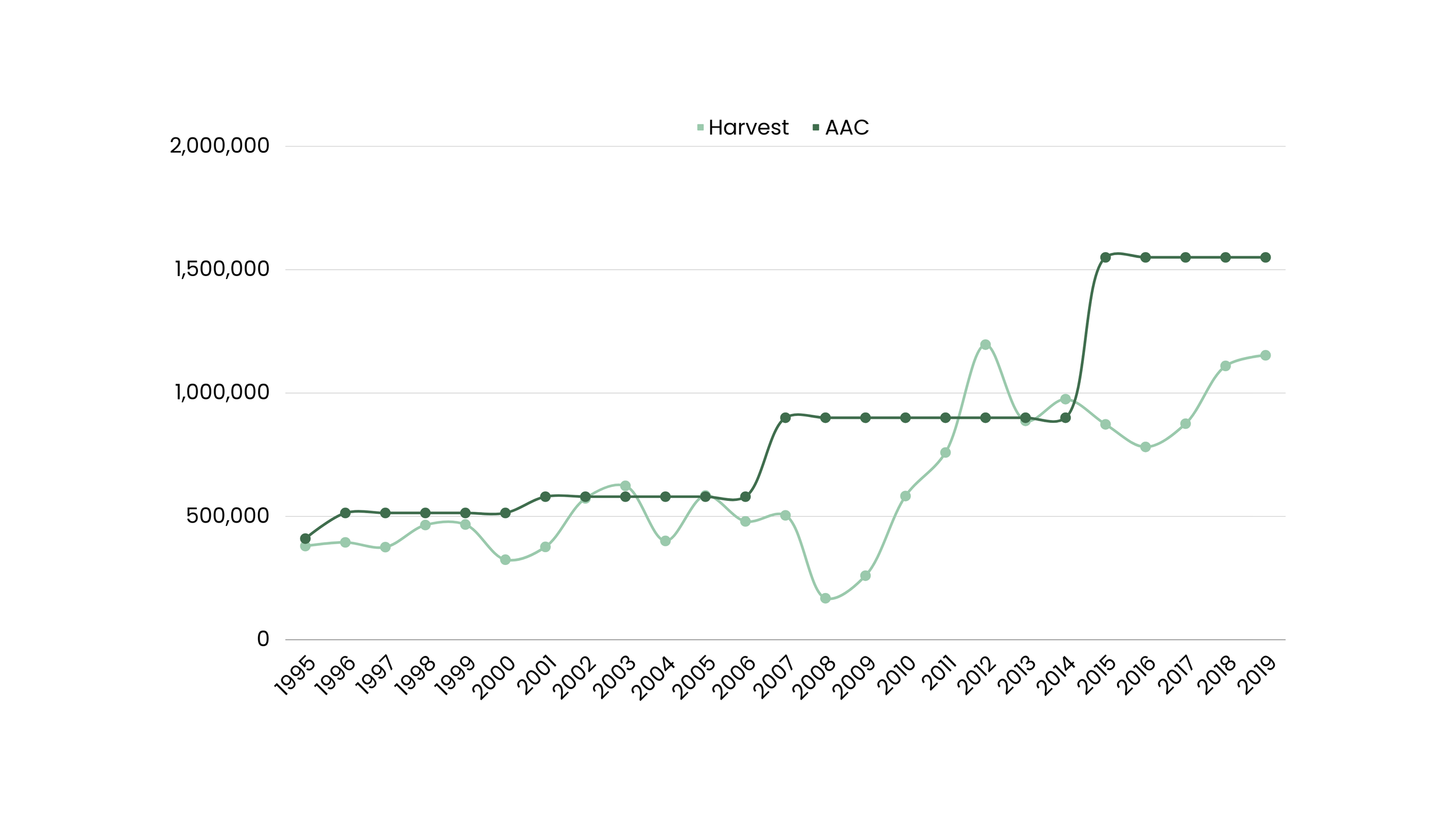

The BC government continues to approve logging in critical caribou habitat across the province. Our research has focused on Tree Farm License (TFL) 48, in the heart of endangered caribou habitat in the Peace River Region, Treaty 8 territory. In TFL 48, the government-authorized harvest levels (Annual Allowable Cut) and the volume harvested maintained their upward trajectory even as these caribou were classified as threatened under the Species At Risk Act when it was enacted in 2003.

Harvest and AAC (in cubic meters) in TFL 48, 1995-2020

three

Governments don’t just approve all these extractive developments; they also subsidise many of them. For example, BC subsidizes coal mining and companies operating oil and gas wells in critical caribou habitat.

Why do governments with formal and professed commitments to caribou recovery continue to approve and even subsidize the developments driving caribou decline?

Key to understanding why governments approve these developments - from forestry, mining, and oil and gas - is understanding who benefits from them.

The prominent narrative about industrial development is that we all benefit from it - there is a “national” or “public” interest in industrial development, which creates jobs, economic growth, money for public goods like education and health care. This public interest is repeatedly invoked as outweighing the harms of these developments.

Promised distribution: public benefits esceeds cost

Does this narrative hold up? Unfortunately the economic forecasts companies make in environmental assessments - forecasts that are arguably the most important ingredient in justifying project approval - are not tracked or reported on. Our audit of these forecasts made for coal mines in endangered central mountain caribou habitat suggests they are significantly inflated.

Less than 60 percent of forecasted jobs materialized - and many appeared to go to out-of-towners. The biggest area of shortfall was taxes - between 1999 and 2019, only 86 million of 250 million in taxes projected materialized. Although access to tax refunds is no longer available since the mines' new owner, Conuma Resources, is privately held, federal data and loans of $120 million, coupled with Conuma’s negative outlook, point to the $86 million in corporate taxes having been refunded, likely bringing the total to zero.

Meanwhile, in forestry, journalist David Broadfield crunched the numbers and found that the cost of government oversight of the industry far outweighs forestry revenues from stumpage.

While forest companies and the government tout the industry’s role as an employment engine in the province, even as harvest levels increase or remain the same, jobs have steadily decreased over the past three decades, consistent with the trend over the past century.

BC Forest Employment per Million Cubic Meters Logged (2001-20219)

If we can use the US as a proxy, there’s good reason to be skeptical of oil and gas benefits too. In the US oil and gas extraction has increased but jobs are decreasing, and job numbers are dramatically over-stated. The American Petroleum Institute claims oil and gas extraction directly employs 2.5 million workers, whereas Food and Water Watch, using government data, found only 541,000 people directly employed - less than 0.4 percent of jobs in the US.

So while the dominant narrative is that the benefits of resource extraction exceed costs (as pictured in the first scale), the reality - at least in some cases - looks more like the scale below.

Actual distribution: public benefits exceed costs

If the public and government do not benefit as much from forestry and mining as government and industry suggest, a new question arises.

Who does benefit from caribou decline?

Above: Caribou on a pipeline in northeast BC. Photo credit: Land Use Department of West Moberly First Nations

These industries do provide jobs and generate revenue for governments. But our audit of coal mining in critical caribou habitat shows that the only major beneficiaries have been mining company shareholders who bought and sold their stock at the right time.

Our research into this question is ongoing, currently focusing on forestry. But this work is challenging to undertake because of data availability: much of the information is privately held or inaccessible from the government.

Ultimately, governments formally and professedly committed to caribou recovery keep authorizing and even fueling the extractive activities causing caribou extinction. They justify this in large part by promising they are acting to the benefit of everyone. But research suggests extraction’s benefits are extremely unevenly distributed. One of the primary aims of our research is to track these benefit flows with the aim of determining where the benefits of extraction in endangered species habitat are flowing and who is receiving them.